Thursday. P. M. — To Decodon Pond.

Erigeron Canadensis, some time. Alisma mostly gone to seed. Thoroughwort, several days. Penthorum, a good while.

Trichostema has now for some time been springing up in the fields, giving out its aromatic scent when bruised, and I see one ready to open.

For a morning or two I have noticed dense crowds of little tender whitish parasol toadstools, one inch or more in diameter, and two inches high or more, with simple plaited wheels, about the pump platform; first fruit of this dog-day weather.

Measured a Rudbeckia hirta flower; more than three inches and three eighths in diameter.

As I am going across to Bear Garden Hill, I see much white Polygala sanguinea with the red in A. Wheeler's meadow (next to Potter's).

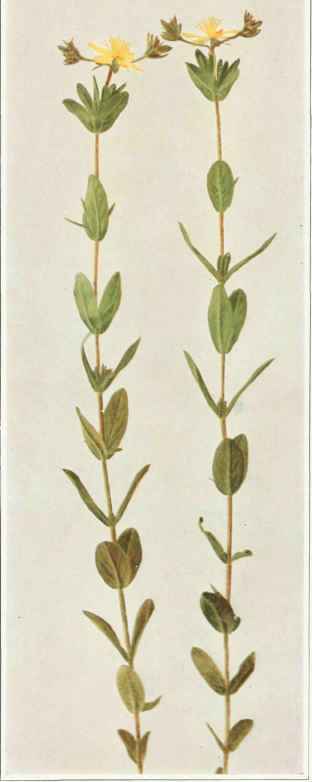

Also much of the Bartonia tenella, which has been out some days at least, five rods from ditch, and three from Potter's fence.

Went through Potter's Aster Radula swamp this dog-day afternoon. As I make my way amid rank weeds still wet with the dew, the air filled with a decaying musty scent and the z-ing of small locusts, I hear the distant sound of a flail, and thoughts of autumn occupy my mind, and the memory of past years.

Some late rue leaves on a broken twig have turned all a uniform clear purple.

How thick the berries — low blackberries, Vaccinium vacillans, and huckleberries — on the side of Fair Haven Hill ! The berries are large, for no drought has shrunk them. They are very abundant this year to compensate for the want of them the last. The children should grow rich if they can get eight cents a quart for blackberries, as they do.

Again I am attracted by the hoary, as it were misty morning light on the base of the upper leaves of the velvety Pycnanthemum incanum. It is the most interesting of this genus here.

The smooth sumach is pretty generally crimson-berried on the Knoll, and its lower leaves are scarlet-tipped (though there are some blossoms yet), but the Rhus copallina there is not yet out.

See dense fields of the great epilobium now in its prime, like soldiers in the meadow, resounding with the hum of bees. The butterflies are seen on the pearly everlasting, etc., etc.

Hieracium paniculatum by Gerardia quercifolia path in woods under Cliffs, two or three days.

Elodea two and a half feet high, how long? The flowers at 3 p. m. nearly shut, cloudy as it is. Yet the next day, later, I saw some open, I think.

Another short-tailed shrew dead in the wood-path.

Near Well Meadow, hear the distant scream of a hawk, apparently anxious about her young, and soon a large apparent hen-hawk (?) comes and alights on the very top of the highest pine there, within gunshot, and utters its angry scream. This a sound of the season when they probably are taking their first (?) flights.

See yellow Bethlehem-star still.

As I look out through the woods westward there, I see, sleeping and gleaming through the stagnant, misty, glaucous dog-day air, i. e. blue mist, the smooth silvery surface of Fair Haven Pond. There is a singular charm about it in this setting. The surface has a dull, gleaming polish on it, though draped in this glaucous mist.

The Solidago gigantea (?), three-ribbed, out a long time at Walden shore by railroad, more perfectly out than any solidago I have seen. I will call this S. gigantea, yet it has a yellowish-green stem, slightly pubescent above, and leaves slightly rough to touch above, rays small, about fifteen.

Mine must be the Aster Radula (if any) of Gray, yet the scales of the involucre are not appressed, but rather sub-squamose, nor is it rare. Pursh describes it, or the Radula, as white-flowered, and mentions several closely allied species.

Wade through the northernmost Andromeda Pond. Decodon not nearly out there. Do I not see some kind of sparrow about the shore, with yellow beneath? Mountain cranberries apparently full grown, many at least.

H. D. Thoreau, Journal, July 31, 1856

Trichostema has now for some time been springing up in the fields, giving out its aromatic scent. See Jujy 31, 1854 ("Blue-curls."); July 11, 1853 ("The aromatic trichostema now springing up"). See also A Book of the Seasons, by Henry Thoreau, Blue-Curls

This dog-day afternoon . . . the air filled with a decaying musty scent and the z-ing of small locusts. See July 31, 1855 ("Our dog-days seem to be turned to a rainy season.") July 31, 1859 ("It is emphatically one of the dog-days. A dense fog, not clearing off till we are far on our way, and the clouds (which did not let in any sun all day) were the dog-day fog and mist, which threatened no rain. A muggy but comfortable day."); July 31, 1860 ("Decidedly dog-days, and a strong musty scent, not to be wondered at after the copious rains and the heat of yesterday.") See also A Book of the Seasons, by Henry Thoreau, Locust, Dogdayish Days and August 2, 1859 ("That fine z-ing of locusts in the grass which I have heard for three or four days is an August sound.")

Another short-tailed shrew dead in the wood-path. See July 12, 1856 (“I have found them thus three or four times before.”)

July 31. See A Book of the Seasons, by Henry Thoreau July 31

Thoughts of autumn occupy my mind, and the memory of past years. See August 7, 1854 ("I am not so much reminded of former years, as of existence prior to years.”) See also Farewell, my friend

Another short-tailed shrew dead in the wood-path. See July 12, 1856 (“I have found them thus three or four times before.”)

July 31. See A Book of the Seasons, by Henry Thoreau July 31

Thoughts of autumn and

the memory of past years

occupy my mind.

A Book of the Seasons, by Henry Thoreau, Thoughts of autumn

A Book of the Seasons, by Henry Thoreau

"A book, each page written in its own season,

out-of-doors, in its own locality."

~edited, assembled and rewritten by zphx © 2009-2024