Many men walk by day --

few walk by night.

It is a very different season.

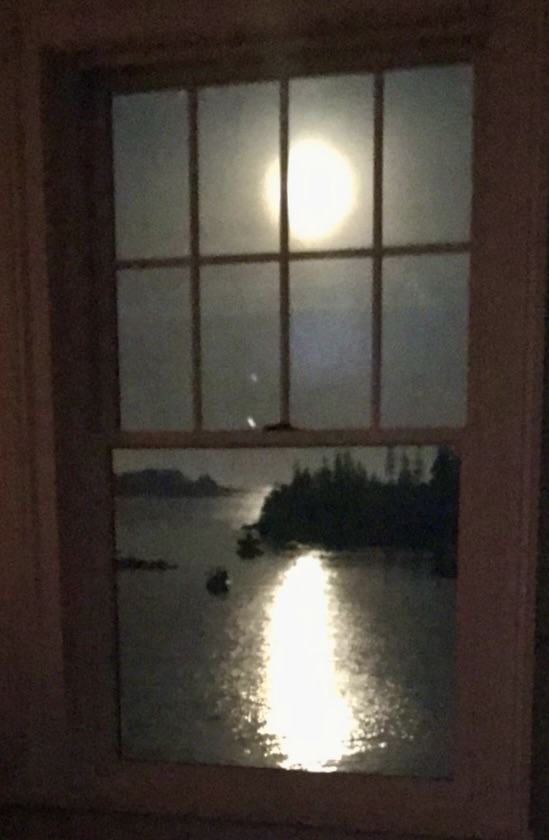

Henry Thoreau, July, 1850

The sun setting red

in haze at the same time as

the full moon rises.

October 8, 1851

October 1. Candle-light. To Conantum. The moon not quite half full. The twilight is much shorter now than a month ago, probably as the atmosphere is clearer and there is less to reflect the light. The air is cool, and the ground also feels cold under my feet, as if the grass were wet with dew, which is not yet the case. I go through Wheeler's corn-field in the twilight, where the stalks are bleached almost white, and his tops are still stacked along the edge of the field. The moon is not far up above the southwestern horizon. Looking west at this hour, the earth is an unvaried, undistinguishable black in contrast with the twilight sky. It is as if you were walking in night up to your chin. There is no wind stirring. An oak tree in Hubbard's pasture stands absolutely motionless and dark against the sky. The crickets sound farther off or fainter at this season, as if they had gone deeper into the sod to avoid the cold. There are no crickets heard on the alders on the causeway. The moon looks colder in the water, though the water-bugs are still active. There is a great change between this and my last moonlight walk. I experience a comfortable warmth when I approach the south side of a dry wood, which keeps off the cooler air and also retains some of the warmth of day. The voices of travellers in the road are heard afar over the fields, even to Conantum house. The stars are brighter than before. The moon is too far west to be seen reflected in the river at Tupelo Cliff, but the stars are reflected. The river is a dark mirror with bright points feebly fluctuating.

I smell the bruised horsemint, which I cannot see, while I sit on the brown rocks by the shore. I see the glow-worm under the damp cliff. No whip poor-wills are heard to-night, and scarcely a note of any other bird. At 8 o'clock the fogs have begun, which, with the low half-moon shining on them, look like cob webs or thin white veils spread over the earth. They are the dreams or visions of the meadow. October 1, 1851

October 1. I do not remember such cold at this season. This is about the full of the moon (it fulled at 9 P.M. the 29th) in clear bright moonlight nights. We have fine and bright but cold days after. October 1, 1860

October 2. A dark and windy night the last. It is a new value when darkness amounts to something positive. October 2, 1858 [new Oct. 7]

October 5. Moon three-quarters full. The nights now are very still, for there is hardly any noise of birds or of insects. The whip-poor-will is not heard, nor the mosquito.There is a down-like mist over the river and pond, and there are no bright reflections of the moon, all the light being absorbed by the low fog.The moon gives not a creamy but white, cold light. Standing on the Cliffs, no sound comes up from the woods. The earth has gradually turned more northward; the birds have fled south after the sun, and this impresses me as a deserted country. October 5, 1851

October 5. The nights now are very still, for there is hardly any noise of birds or of insects . . . The howling of the wind about the house just before a storm to-night sounds like a loon on the pond. October 5, 1853

October 5. The comet makes a great show these nights. Its tail is at least as long as the whole of the Great Dipper, to whose handle, till within a night or two, it reached, in a great curve, and we plainly see stars through it. October 5, 1858 [new Oct 7]

October 6. 7.30 P. M. – To Fair Haven Pond by boat, the moon four-fifths full, not a cloud in the sky; paddling all the way. The water perfectly still, and the air almost, the former gleaming like oil in the moonlight, with the moon's disk reflected in it . . . The river appears indefinitely wide; there is a mist rising from the water, which increases the indefiniteness. A high bank or moonlit hill rises at a distance over the meadow on the bank, with its sandy gullies and clamshells exposed where the Indians feasted. The shore line, though close, is removed by the eye to the side of the hill. It is at high-water mark. It is continued till it meets the hill. Now the fisherman's fire, left behind, acquires some thick rays in the distance and becomes a star. . . . Such is the effect of the atmosphere. The bright sheen of the moon is constantly travelling with us, and is seen at the same angle in front on the surface of the pads; and the reflection of its disk in the rippled water by our boat-side appears like bright gold pieces falling on the river's counter. This coin is incessantly poured forth as from some unseen horn of plenty at our side . . . I do not know but the weirdness of the gleaming oily surface is enhanced by the thin fog. A few water-bugs are seen glancing in our course . . . As we rowed to Fair Haven's eastern shore, a moonlit hill covered with shrub oaks, we could form no opinion of our progress toward it, — not seeing the water line where it met the hill, – until we saw the weeds and sandy shore and the tall bulrushes rising above the shallow water ( like ) the masts of large vessels in a haven. The moon was so high that the angle of excidence did not permit of our seeing her reflection in the pond. As we paddled down the stream with our backs to the moon, we saw the reflection of every wood and hill on both sides distinctly. These answering reflections-shadow to substance-impress the voyager with a sense of harmony and symmetry, as when you fold a blotted paper and produce a regular figure, - a dualism which nature loves. What you commonly see is but half. Where the shore is very low the actual and reflected trees appear to stand foot to foot, and it is but a line that separates them, and the water and the sky almost flow into one another, and the shore seems to float. As we paddle up or down, we see the cabins of muskrats faintly rising from amid the weeds, and the strong odor of musk is borne to us from particular parts of the shore. Also the odor of a skunk is wafted from over the meadows or fields. The fog appears in some places gathered into a little pyramid or squad by itself, on the surface of the water. Home at ten. October 6, 1851

October 8. The sun set red in haze, visible fifteen minutes before setting, and the moon rose in like manner at the same time . . . There is more fog than usual. The moon is full. The tops of the woods in the horizon seen above the fog look exactly like long, low black clouds, the fog being the color of the sky. October 8, 1851

October 10. The elms in the village have lost many of their leaves , and their shadows by moonlight are not so heavy as last month. October 10, 1851 [full]

October 14. Balloonists speak of hearing dogs bark at night and wagons rumbling over bridges. October 14, 1859 [full Oct. 11]

October 16. The new moon, seen by day, reminds me of a poet's cheese. October 16, 1851

October 16. Hunter's Moon. Walk to White Pond. October 16, 1853 [full Oct. 17]

October 17. Very high wind in the night, shaking the house. . . . Some rain also, and these two bring down the leaves. October 17, 1857

October 22. The haze is still very thick, though it is comparatively cool weather, and if there were no moon to-night, I think it would be very dark. Do not the darkest nights occur about this time, when there is a haze produced by the Indian-summer days, succeeded by a moonless night? October 22, 1858 [full]

October 28. 8 p.m.— To Cliffs.After whatever revolutions in my moods and experiences, when I come forth at evening, as if from years of confinement to the house, I see the few stars which make the constellation of the Lesser Bear in the same relative position, - the everlasting geometry of the stars. The moon beginning to wane. It is a quite warm but moist night. The dew in the withered grass reflects the moonlight like glow-worms. That star which accompanies the moon will not be her companion tomorrow . . . From the Cliffs the river and pond are exactly the color of the sky . . . Even the distant fields across the river are seen to be russet by moonlight as by day and the young pines near by are green. October 28, 1852 [ full 27th]

October 30. There’s a very large and complete circle round the moon this evening, which part way round is a faint rainbow. It is a clear circular space, sharply and mathematically cut out of a thin mackerel sky. You see no mist within it, large as it is, nor even a star. October 30, 1857 [full Nov. 2]

On Sunday, October 8, 1854 Thoreau gave his lecture "Moonlight" to a small audience of friends, among them Bronson Alcott. James Spooner, and Marston Watson and his wife Mary Russell Watson. See Thoreau's Lectures after Walden 259-255. See also Night and Moonlight (first published in the Atlantic Monthly, November 1863)

See also:

A Book of the Seasons, by Henry Thoreau, June Moonlight

A Book of the Seasons, by Henry Thoreau, July Moonlight

A Book of the Seasons, by Henry Thoreau, August Moonlight

A Book of the Seasons, by Henry Thoreau, September Moonlight

A Book of the Seasons, by Henry Thoreau, October Nights and Moonlight

A Book of the Seasons, by Henry Thoreau

"A book, each page written in its own season,

out-of-doors, in its own locality."

~edited, assembled and rewritten by zphx © 2009-2022